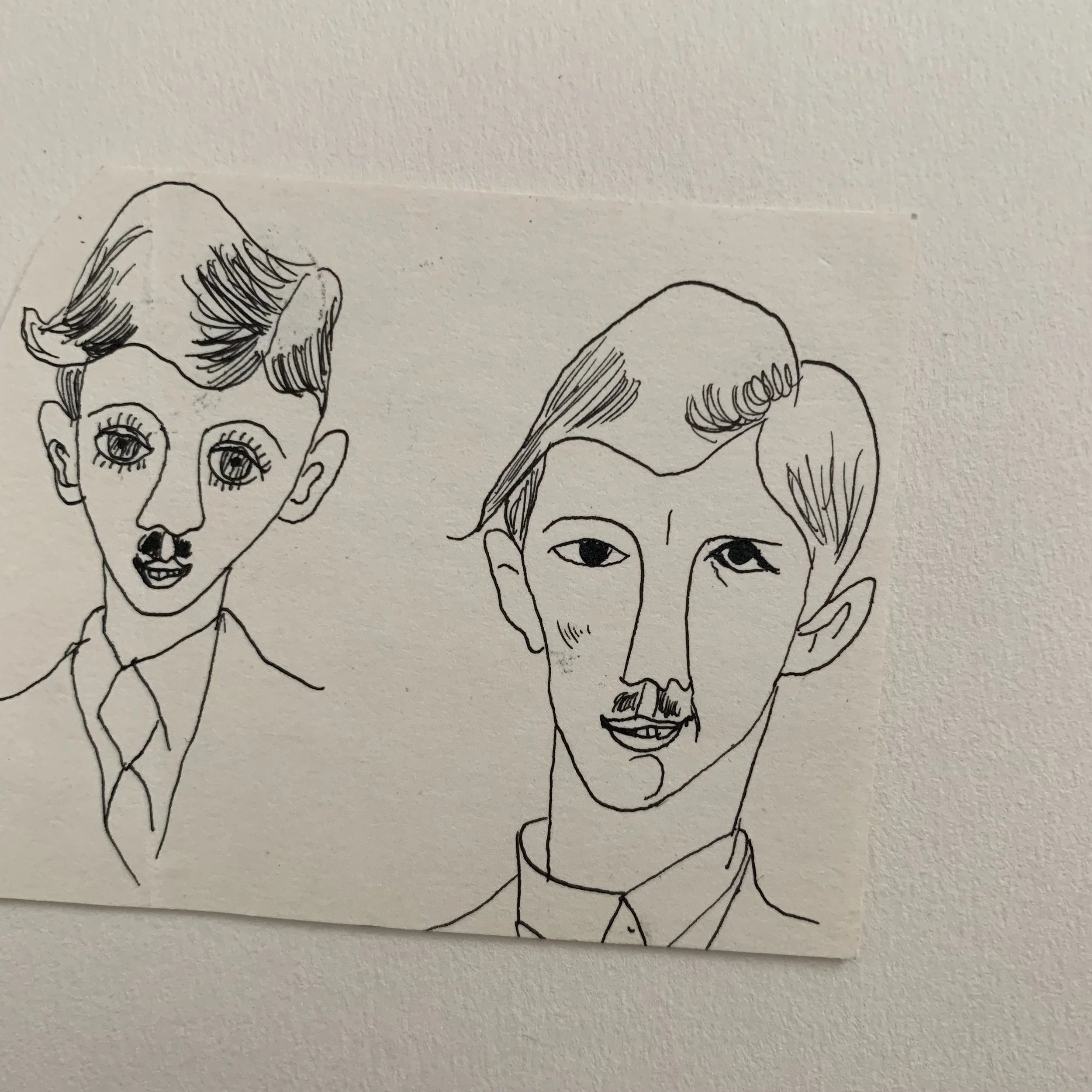

Mathieu ROSIANU (1897-1969)

Mathieu ROSIANU (1897-1969)

Deux têtes d’hommes, circa 1930

Encre sur papier

7 x 9 cm

cadre : 18 x 24 cm

-

Two men's heads, circa 1930

Ink on paper

7 x 9 cm

frame: 18 x 24 cm

Né à Bucarest en 1897 d’un père officier de la garde nationale roumaine et d’une mère d’origine française, Mathieu Rosianu grandit dans un milieu bourgeois. Il obtient un premier diplôme de dessin en 1912. Il quitte la Roumanie en 1918 pour s’installer à Paris où il poursuit sa formation artistique aux Arts décoratifs avant d’être admis à l’École des beaux-arts en 1920 dans l’atelier d’Ernest Laurent (1859-1929). En 1923, il expose ses premières toiles au Salon d’Automne, au Salon des Tuileries et au Salon de la Société nationale des beaux-arts.

À l’aube des années 1930, Mathieu Rosianu travaille comme dessinateur chez Bitschenauer et chez Schweitzer avant de fonder sa propre maison de dessins pour tissus. Il produit de nombreux modèles pour d’importantes entreprises de textile françaises et américaines. Politiquement engagé, il fréquente des artistes proches de la mouvance communiste libertaire tels que Jean Hélion avec lequel il se lie d’amitié. En 1931, il participe aux réunions de l’Union des artistes professionnels du Groupe Artistique qui rassemble des artistes soutenant la revue Monde, hebdomadaire fondé par Henri Barbusse.

Dès 1932, Mathieu Rosianu compte parmi les membres fondateurs de l’Association des Écrivains et Artistes Révolutionnaires (A.E.A.R.) créée cette même année et réunissant des artistes engagés que sont Jean Lurçat, Jean Hélion, Auguste Herbin ou encore Édouard Pignon. Il contribue à la revue de l’A.E.A.R., Commune, pour laquelle il réalise avec son épouse Juliette Bajou plusieurs compositions graphiques. Très impliqué, il fait partie du comité d’initiative du collectif et participe à ce titre activement à l’organisation de la première Exposition des Artistes Révolutionnaires qui a lieu en 1934 et à laquelle prend part une dizaine d’artistes dont Francis Jourdain, Amédée Ozenfant et Auguste Herbin. Mathieu Rosianu rédige notamment la préface du catalogue de celle-ci, comme un manifeste. La même année, ses œuvres côtoient celles d’artistes surréalistes de renom que sont Salvador Dali et Man Ray à l’occasion de l’exposition intitulée Avertissement chez Marie Cuttoli, Galerie Vignon à Paris, et dont le propos s’inscrit en réaction à l'attitude des nazis envers l’art dit “dégénéré”.

En 1935, Mathieu Rosianu prend ses distances à l’A.E.A.R. et se consacre à la réalisation de projets décoratifs de soieries et de papiers peints sous le pseudonyme d’Émile Arbor. Ses créations rencontrent un vif succès à l’Exposition Universelle de 1937 où il se voit récompensé d’un Grand Prix avant que la Seconde Guerre mondiale ne vienne mettre un terme à cette activité.

Fidèle à la figuration, Mathieu Rosianu est soucieux de renouer avec la réalité chère aux artistes de l’entre-deux-guerres. Il s’attache à exalter la dignité des classes populaires et son œuvre s’inscrit en grande partie dans la mouvance d’artistes soulevant le rôle social de l’art. En opposition avec la peinture dite “de chevalet”, il est partisan d’une “peinture pour tous”*, une “peinture chargée d’émotions humaines”* et non pas une “peinture prétexte”*.

Le traumatisme de l’effroyable désastre des deux guerres et la souffrance qui s’empare de lui inspirent à l’artiste une œuvre plus sombre. Sa souffrance psychique s’exprime dans sa peinture qui demeurera pour lui une nécessité vitale. Il développe une obsession certaine pour des thèmes relatifs à l’obsession de la mort, à l’angoisse de la déconstruction et au deuil de l’enfant.

Born in Bucharest in 1897 to an officer in the Romanian National Guard and a mother of French origin, Mathieu Rosianu grew up in a bourgeois milieu. He obtained his first drawing diploma in 1912. He left e Romania in 1918 to settle in Paris, where he continued his artistic training at the Arts Décoratifs before being admitted to the École des Beaux-Arts in 1920 in the studio of Ernest Laurent (1859-1929). In 1923, he exhibited his first paintings at the Salon d'Automne, the Salon des Tuileries and the Salon de la Société nationale des beaux-arts.

At the dawn of the 1930s, Mathieu Rosianu worked as a draftsman for Bitschenauer and Schweitzer, before setting up his own fabric design company. He produced numerous designs for major French and American textile companies. Politically committed, he frequented artists close to the libertarian communist movement, such as Jean Hélion, with whom he became friends. In 1931, he took part in meetings of the Union des artistes professionnels du Groupe Artistique, a group of artists who supported the magazine Monde, a weekly founded by Henri Barbusse.

In 1932, Mathieu Rosianu was one of the founding members of the Association des Écrivains et Artistes Révolutionnaires (A.E.A.R.), created that same year and bringing together such committed artists as Jean Lurçat, Jean Hélion, Auguste Herbin and Édouard Pignon. He contributes to the A.E.A.R. magazine Commune, for which he and his wife Juliette Bajou produce several graphic compositions. Highly involved, he was a member of the collective's initiative committee, actively participating in the organization of the first Exposition des Artistes Révolutionnaires, held in 1934 and attended by a dozen artists including Francis Jourdain, Amédée Ozenfant and Auguste Herbin. Mathieu Rosianu wrote the preface to the catalog, like a manifesto. The same year, his works were exhibited alongside those of renowned Surrealist artists Salvador Dali and Man Ray at the Avertissement exhibition at Marie Cuttoli's Galerie Vignon in Paris, in reaction to the Nazis' attitude towards so-called "degenerate" art.

In 1935, Mathieu Rosianu distanced himself from the A.E.A.R. and devoted himself to the creation of decorative silk and wallpaper projects under the pseudonym Émile Arbor. His creations met with great success at the 1937 Exposition Universelle, where he was awarded a Grand Prix, before the Second World War put an end to this activity.

Faithful to figuration, Mathieu Rosianu is keen to reconnect with the reality so dear to the artists of the interwar period. His aim was to exalt the dignity of the working classes, and his work is largely in line with the movement of artists raising the social role of art. In opposition to so-called "easel painting", he advocated "painting for all "*, "painting charged with human emotion "* and not "pretext painting "*.

The trauma of the terrible disasters of the First and Second World Wars, and the suffering that took hold of him, inspired the artist to produce darker works. His psychic suffering found expression in his painting, which remained for him a vital necessity. He developed a definite obsession with themes relating to the obsession of death, the anguish of deconstruction and the mourning of the child.